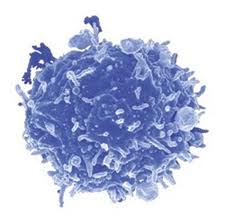

Ipilimumab is an anti-CTLA-4 antibody used for treatment of metastatic melanoma, one of only two cancer immunotherapeutic drugs approved to date by the FDA. CTLA-4 is a negative regulatory molecule expressed by activated T cells as well as by negative regulatory T cells (TREGs). CTLA-4 is related to the T cell co-stimulatory receptor CD28, and acts to suppress T cell function by competing with CD28 for binding to CD80 and CD86 on antigen presenting cells and recruiting inhibitory molecules into the TCR signaling synapse. Thus, the mechanism of action of Ipilimumab has been presumed to involve releasing anti-tumor effector T cells from CTLA-4-inhibition and/or limiting TREG activity in the tumor and therefore resulting in an increase in the ratio of effector T cells/ TREGs within the tumor. However, two recent articles demonstrate that Ipilimumab has an additional mechanism of action: FcgR-dependant depletion of intra-tumoral TREGs.

Fcg receptors are a multi-family class of immunoglobulin (IgG)-binding receptors that initiate either activating or inhibitory signals when engaged. Activating receptors contain cytoplasmic immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs (ITAM) and activate the FcgR-expressing cell to mediate functions including antibody-dependant cell mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) and phagocytosis of the antibody-labeled target cell. FcgRIIB is the single inhibitory Fcg receptor in mice and humans and contains a cytoplasmic immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif (ITIM) which instead downregulates cellular responses. There are four classes of IgG molecules in both humans and mice, and each bind to different Fcg receptors with varying affinity. Thus differential affinities of IgG subclasses to functionally different Fcg receptors are thought to mediate the variation in clinical effectiveness of different antibodies targeting the same antigen.

Ipilimumab functions to increase the ratio of effector T cells to TREGS in the tumor microenvironment and has been shown to require binding to both types of T cells for maximal anti-tumor effectiveness. However, how Ipilimumab differentially modulates these cell types remains to be understood. A recent study published in The Journal of Experimental Medicine by Simpson et. al sought to clarify the mechanism by which Ipilimumab functions to alter the ratio of effector T cells/ TREGs in a murine tumor model. Interestingly, the effects of Ipilimumab were found to be tissue-dependant. In tumors which had high levels of infiltrating CD11b+ macrophages expressing the ADCC-activating FcgRIV, TREGS were selectively depleted in an FcgR-dependant manner, while effector T cells were instead expanded. In lymph nodes lacking significant levels of these macrophages, frequencies of both effector T cells and TREGS were increased. Tumor-associated TREGS expressedhigher levels of CTLA-4 than their effector T cell counterparts, or than TREGS present in the lymph node, indicating that higher CTLA-4 expression levels mediate ADCC via macrophages in the tumor. Furthermore, the presence of FcgRs and hence TREG depletion was required for Ipilimumab’s effects. Thus is appears that the mechanism of action of Ipilimumab on the effector T cell compartment is two-fold: directly targeting effector T cells to release inhibition via blocking CTLA4 activity, as well as by ADCC-mediated depletion of TREGS.

A second article in the same issue of The Journal of Experimental Medicine by Bulliard et al also explored the role of FcgR engagement on the effects of Ipilimumab as well as an agonistic antibody (DTA-1) targeting the T cell activating receptor GITR (TNFR glucocorticoid-induced TNFR-related protein), which is also expressed on both activated T cells and TREGs. This study concluded that a major mechanism of action for both antibodies involved engagement of activating FcgRs leading to ADCC-mediated TREG depletion from the tumor. Even though GITR-activation in effector T cells promotes activities including cytokine production and proliferation, the agonistic properties of this antibody alone were not effective in the absence of activating FcgR engagement. Thus, even for functionally different (antagonistic versus agonistic) immunotherapeutic antibodies targeting these same T cell populations, FcgR-mediated ADCC of TREGs appears to be a critical mechanism for anti-tumor effects.

These studies highlight several important principles for the field of tumor immunotherapeutics. Antibody targeting can elicit multiple effects, dependant on expression levels of the target, the isotype of the antibody, and the FcgR-expressing cell types present in the tissue. Thus knowing the nature of the immune populations present in various types of tumors that are able to mediate ADCC, the FcgRs expressed by these cells, and the expression levels of the target molecule on immune populations that would be ideally targeted for elimination versus activation/inhibition will be critical areas for the forwarding of this field. Furthermore, as FcgRs are polymorphous in humans, and affect IgG binding affinities, taking these genetic variations into account will be critical in the future of personalized medicine.

Further reading:

Fc-dependent depletion of tumor-infiltrating regulatory T cells co-defines the efficacy of anti-CTLA-4 therapy against melanoma. Simpson TR, Li F, Montalvo-Ortiz W, Sepulveda MA, Bergerhoff K, Arce F, Roddie C, Henry JY, Yagita H, Wolchok JD, Peggs KS, Ravetch JV, Allison JP, Quezada SA. J Exp Med. 2013 Jul 29.

Activating Fc γ receptors contribute to the antitumor activities of immunoregulatory receptor-targeting antibodies. Bulliard Y, Jolicoeur R, Windman M, Rue SM, Ettenberg S, Knee DA, Wilson NS, Dranoff G, Brogdon JL. J Exp Med. 2013 Jul 29.

Fcgamma receptors as regulators of immune responses. Nimmerjahn F, Ravetch JV. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008 Jan;8(1):34-47.